As far as I am concerned, the game was up when Joseph Weizenbaum programmed ELIZA in 1966. ELIZA, a deceptively simple chatbot, convinced counterparties it was human through scripts that generated canned responses. ELIZA reflects back what people type to it, producing a simulacrum of an active listener. ELIZA works technically by re-ordering the user’s inputs in the form of a question. Its conversational script detects the most important components of the input sentence – for example, the “love to fly kites” part of “I love to fly kites” – and then transforms them into a question with slightly altered pronouns and verbs to get “so, you love to fly kites. What do you feel about that?” Weizenbaum was horrified that people treated the chatbot as if it was a real human therapist, and even more horrified that real doctors started to recommend automated therapy as the “technology of the future.” For tech critics, ELIZA is a parable about the dangers of technological dehumanization or more narrowly the dangers of producing machines that can fool humans. Naturally I have a different perspective.

First, I should note that what it means for people to be credulous about something that seems obviously fake to us is complicated. Emily Ogden, summarizing her history of 19th century “animal magnetism” spiritualism, observes the following about famous paranormalist Loraina Brackett:

Brackett couldn’t see well enough to support herself through work. She needed to depend on friends and charitable strangers. That meant she needed to present herself in a way that accorded with their understanding of the social role ‘blind person’. If they could not accept that someone who was blind – and thus legitimately in need of assistance – might be able to see in a limited way, or might be able to move around confidently, then she would have been obliged to curtail these activities. The late disability theorist Tobin Siebers called this the ‘masquerade’ of disability: the obligation to perform the disability, sometimes overperform it, so that it would be legible enough to secure the assistance that one genuinely needs. Let’s say that ordinary life involved a masquerade of disability for Brackett. In that case, animal magnetism, because it demanded that each participant in a seance play along with the suggestions of the others, might have been freeing for her to some extent. Animal magnetism was a way of formalising a common human capacity for suspending judgment and playing along in the name of social bonds. ..It isn’t belief, not really; it’s neither believing or disbelieving, but bonding through the construction of a shared story.

If you are interested in more discussion of these complexities, I recommend the new edited volume on digital media and human belief by Simone Natale and Diana Pasulka. Suffice to say its also very complicated. Belief can encompass pragmatic belief in the functioning of digital systems, belief in the qualitative distinction of digital systems, belief that digital systems will change humanity, and belief that digital technologies will allow for transcendence of mortal constraints. These beliefs have varied secular and religious expressions. And they occur in the background of the processes I allude to here and here. But this is not quite what I’m interested in. Let’s remove complexity from all of this and just assume there is a substitution effect. So I said the “game was up” because I believe that almost all of the supposed world-ending technological advances to come (deepfakes, generative text, what have you) are just mopping up after the battle ELIZA won. And ELIZA won that battle by giving people something they increasingly get less and less in “real” life: someone that at least simulates caring about them. It “listens” to them and then asks further questions about their condition.

There’s an argument that its unreal precisely because it overproduces the real – that its a much more exaggerated version of the real thing. Therefore our need for it is somehow illegitimate or compromised. It is our revealed preference, but in the same way getting high is a junkie’s “revealed preference.” I have problems with this argument. To be sure, this is not an endorsement of the idea of revealed preference as the Archimedes lever of human behavior. Preferences can be shaped or created in action, to say nothing of the conundrum of akrasia or scientific debates about limits to epistemic and instrumental rationality. So if you think that people have strange, abnormal, or malign revealed preferences what then? My last post, on a completely different subject – President Trump – is accidentally relevant here. If you assume that Trump has no real fixed preferences or ability to conceive of himself as an separable agent within the world, then you cannot treat him with the deference and respect normally afforded to autonomous and rational individuals. Instead you, in an ideal world, would keep him as far away from anything consequential as humanly possible.

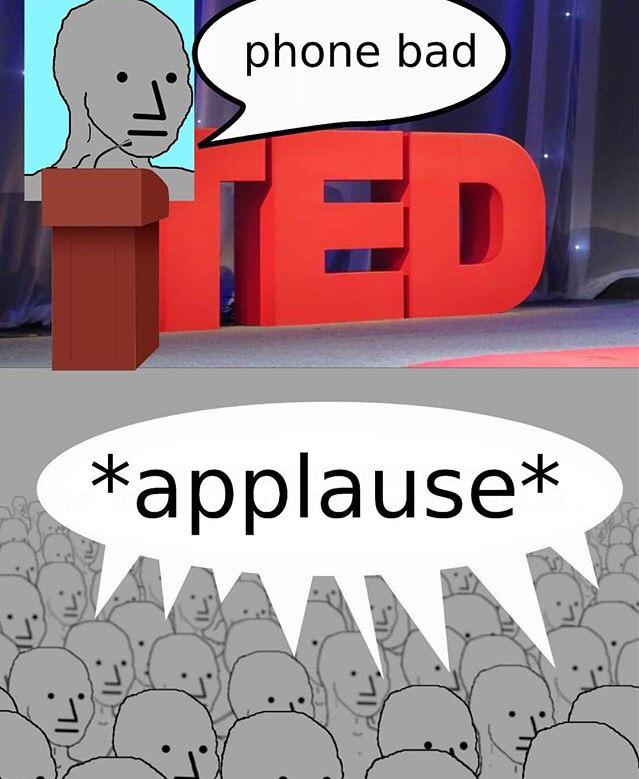

But this extreme case aside, there are plenty of more ordinary ways in which people often fail to meet normative standards of rational and informed behavior. The problem with assumptions of limitations to choice is the need for paternalism and the reduction of freedom, as well as perhaps – echoing Ogden’s note earlier – uncertainty about how particular forms of seemingly abnormal behaviors can be interpreted very differently depending on the observer. Finally, add in the difficulty in demonstrating the causality of “harm” from the thing preferred in some cases and you have another conundrum. And regardless there’s something else missing from the argument: a recognition that the “real thing” being substituted for is unevenly distributed both in basic availability and quality. ELIZA is not the same as a “real” conversational partner, but this is also like saying that Olive Garden is not the same thing as a French bistro with a five-star Zagat rating. The depressingly common error of tech analysis is the comparison of an imperfect technical substitute for an idealized human original. Hence the technopanic about automated simulacrum of intimacy is in part also a desublimation of generalized inequalities in intimacy and interpersonal bonds.

I am not going to get into the various sociological debates about shifts in the availability of interpersonal and group bonds in modern societies. Let us dispense with that for a moment and just note that there are many people who find it difficult to impossible to form the bonds they wish with others. For some this is due to immutable personal characteristics, for others it is a consequence of their own choices, and for others still it is simply an artifact of external circumstances independent of their characteristics and behavior. For many more it is a mixture of the three. This will always be the case even in the best of all possible worlds. What of these people? Additionally, most of us will find that there are always limits to the abilities of others to fulfill deep and enduring needs we have, and that we can run up against these limits at the times we need our needs fulfilled the most. Again, this is simply a fact of life. What then? Whenever I monitor conversations about this topic, I detect a deep sense of unease that comes out in often clumsy and ugly ways. The unease comes from the inevitable friction over who is deserving, what they deserve, what we owe to them, and what costs we must bear in doing so.

When a celebrity commits suicide, there’s a superficial outpouring of “check on your friends” messages which is then promptly followed by the usual diktat about purging “toxic friends” from your life. The concept of “emotional labor” once began as a useful description of unpaid services offered by retail employees, but soon became an all-encompassing expression of discontent at bearing the costs of interpersonal interaction with others. These sorts of reactions are extreme but they get at a fundamental and unavoidable problem, which is that its difficult to talk about human needs without invoking the question of who ought to satisfy them and how. And at that point people become understandably wary, nervous, and anticipate a demand that they be the ones to do so. Less charitably, it looks similar to political propaganda about “welfare queens” driving Cadillacs to get food stamps. Any appreciation of deprivation becomes drowned out by fear of and revulsion at being exploited by moochers. Moochers everywhere, out to mooch without properly “paying their dues” and such. Society has gone mad! Either way, its impossible to talk about this without getting into subjective, emotional, and discomforting issues that often trigger screaming and shouting.

And, let’s face it. We all imagine ourselves as entitled to things but denounce others as entitled. And we all tend to also underestimate luck in thinking about the good things in our lives. Again, eternal human problems that are unlikely to go away anytime soon. We can’t really make up our minds about what we want, what we’re willing to give up in return for it, and what we’re willing to tolerate if we aren’t willing to give things up. The thing is that technology does not wait for humans to make progress on “eternal human problems.” It is the aggregate of material economic, scientific, and engineering advances, subjective (social, cultural, economic) choices. It is also the aggregate of limited but still important abilities of individual entrepreneurs to predict or dream up future human needs and influence and mold existing ones. Moreover, the history of innovation – both licit and illicit – is a history of arbitraging gaps between what human societies claim they prioritize in speech and writing and what they end up actually prioritizing via their action and behavior. We say we want one thing, but we end up doing something else or otherwise just contradicting ourselves via inaction.

Upset that children spend so much time in Fortnite? Perhaps it might be easier for them to socialize the traditional way if adults did not actively and passively constrain them from doing so. Actively in that unaccompanied children doing anything that might produce a lawsuit or agitate an older observer gets quickly referred to law enforcement and other punitive authority figures. Passively in that children being pushed to crunch in and out of school makes it easier to interact with their friends virtually than physically. But unwillingness to see the child’s need itself as legitimate – and more importantly failure to take responsibility for how the need being met is shaped by collective adult choices – tends to blend in with more understandable fears about the negative effects of digital media on people too young to fully make informed decisions about their lives. Adults of course may say they want the best for their children but their children may feel otherwise (and not necessarily incorrectly). Whatever effects Fortnite may or may not have are easier to single out than the fundamental contradiction between these two differing adult and child perceptions.

Similarly, it’s so much easier to be afraid of things like ELIZA than to actually do anything about our inconsistent values and behaviors and the way they relate to our complicated and diverse needs and desires. If you find ELIZA and her machine children threatening the best you can do individually is to try to be better to your fellow humans. I am sure you already know how – there are people in your own life who could benefit from your love and care. It’s corny to say but try to pay it forward. Collectively, it may be wise to consider what kinds of environments creatures like ELIZA seem to habitually cluster around and why such environments make them more likely to be perceived as equal to humans. These environments seem to be proliferating at a rapid clip, so more ELIZAs likely will follow in their wake. I am not saying that there are no ethical questions involved in making machines like ELIZA (Weizenbaum’s own thoughts on this remain unparalleled). I am saying that as long as there is a gap to be arbitraged, it will be arbitraged, and how we individually and collectively respond to that inevitability is the most important matter to be decided. And, as painful as it may be at times, part of the response must involve taking stock of our own role in creating the gap being exploited to begin with.